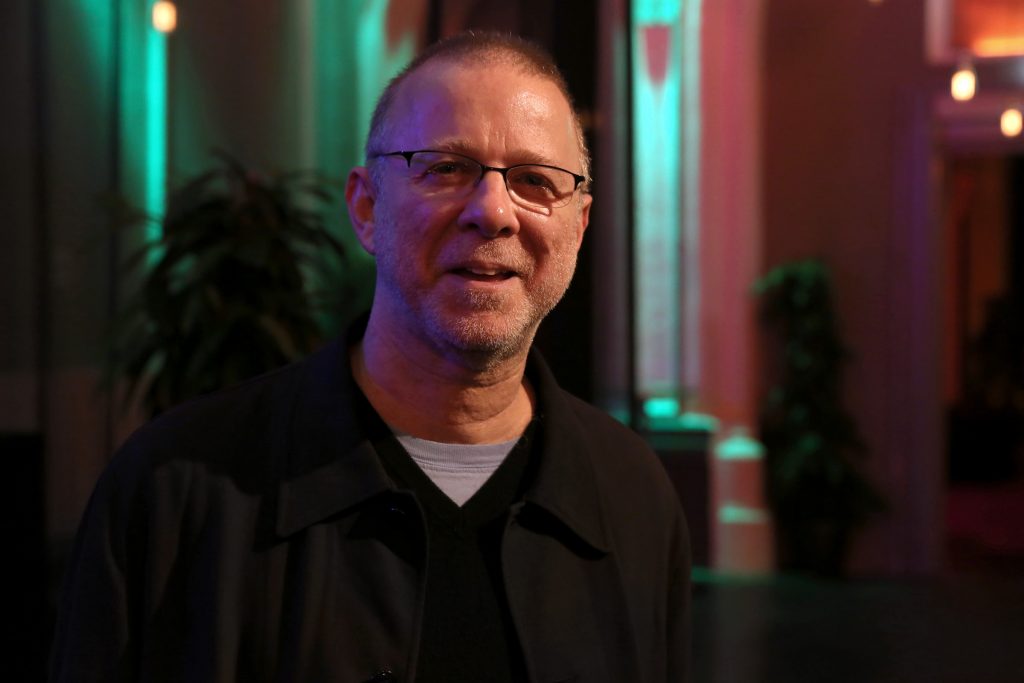

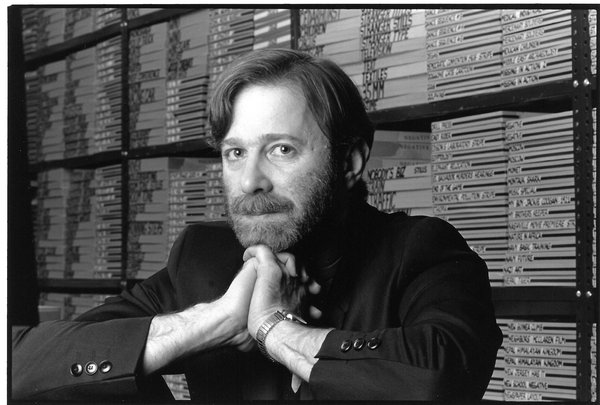

There is no easy way to describe the work of American independent filmmaker Alan Berliner.

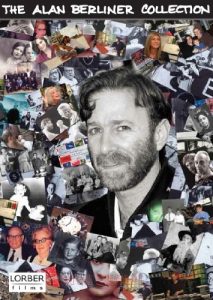

I recently got the DVD box set that included five of his films. On the box, The New York Times is quoted saying “Alan Berliner illustrates the power of fine art to transform life.” After watching them all, I would agree, but there’s really no pinning it down. His feature films are described in many different ways from “experimental documentaries” to “personal nonfiction” to “cine-essays” but Berliner’s signature style is unmistakable and the same themes persistently come up.

I recently got the DVD box set that included five of his films. On the box, The New York Times is quoted saying “Alan Berliner illustrates the power of fine art to transform life.” After watching them all, I would agree, but there’s really no pinning it down. His feature films are described in many different ways from “experimental documentaries” to “personal nonfiction” to “cine-essays” but Berliner’s signature style is unmistakable and the same themes persistently come up.

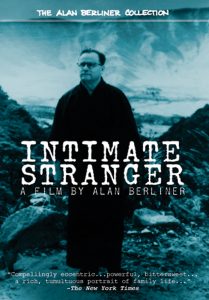

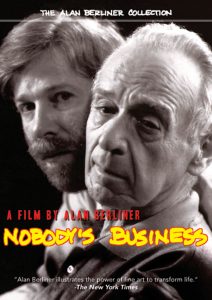

Layers of psychological and emotional elements motivate Berliner to look at his life in new ways through his films. To say his film Intimate Stranger (1991) is all about his maternal grandfather and Nobody’s Business (1996) is only about his father, it leaves so much out of what the film is truly about. Berliner himself has said that he realized a film about his father “could also be about love and family and memory and identity and again, about the unspoken contracts that bind parents and children, and siblings and cousins…a biography of this one ordinary man – can be the crossroads where all these things intersect.”

Layers of psychological and emotional elements motivate Berliner to look at his life in new ways through his films. To say his film Intimate Stranger (1991) is all about his maternal grandfather and Nobody’s Business (1996) is only about his father, it leaves so much out of what the film is truly about. Berliner himself has said that he realized a film about his father “could also be about love and family and memory and identity and again, about the unspoken contracts that bind parents and children, and siblings and cousins…a biography of this one ordinary man – can be the crossroads where all these things intersect.”

His is a cinematic experience full of the invisible lightning energy of splicing one unlikely image after another. The current this friction creates carries the viewer through. It works with the audience to make visual meaning to the oral stories.

Berliner became known internationally with The Family Album (1986), a collage film composed of found clips from rare, anonymous 16mm home movies from the 1920s to 1950s that he found in flea markets and garage sales.

Underscored by amateur family recordings, audio interviews, and structured from birth to death; the film lays out the material as a composite lifetime.

A PDF book is included in the Alan Berliner DVD Collection with Anne S. Lewis’s interview with Berliner for Colgate University, in which he said, at screenings of the The Family Album, people started talking as if he was an expert on Family. He said making the film “not only activated my fascination with family issues, but also pushed me to look closer at my own.”

A PDF book is included in the Alan Berliner DVD Collection with Anne S. Lewis’s interview with Berliner for Colgate University, in which he said, at screenings of the The Family Album, people started talking as if he was an expert on Family. He said making the film “not only activated my fascination with family issues, but also pushed me to look closer at my own.”

I am personally speculating that perhaps the initial spark that propelled his curiosity with American families was rooted from the early experience of his parents’ divorce. I find it interesting that his films are all intensely personal but his parents’ divorce is often glossed over. His parents almost always appear in all in his films but never together (except in old home movies.)

Perhaps, Berliner became fascinated with eavesdropping on the lives of other families through nostalgic home movies when his own idyllic family self-image began to fracture.

The Sweetest Sound (2001) is about all the other men he could find named Alan Berliner and WIDE AWAKE (2006) is about his lifelong struggle with insomnia. He turned his camera finally and unflinchingly onto himself to reveal a kind of fractured soul as perhaps a result of that trauma. He said “By using my life as a living laboratory, I want to make viewers reflect upon similar circumstances or issues in theirs.”

The Sweetest Sound (2001) is about all the other men he could find named Alan Berliner and WIDE AWAKE (2006) is about his lifelong struggle with insomnia. He turned his camera finally and unflinchingly onto himself to reveal a kind of fractured soul as perhaps a result of that trauma. He said “By using my life as a living laboratory, I want to make viewers reflect upon similar circumstances or issues in theirs.”

Each film in his oeuvre is edited in a staccato style punctuated by the click-clack of a manual typewriter. Berliner’s surrealist nonfiction cinema is like being inside the narrator’s head while they’re half-dreaming.

Sometimes, it’s like William S. Burroughs meets Sergei Eisenstein.

Archival footage is Berliner’s vocabulary of dream language; he re-invents the grammar of the movies with filing cabinets filled with footage tagged in various categories. He uses them like the alphabet in his own cinematic foundry.

Again from his interview with Anne S. Lewis, Alan Berliner is quoted:

“I continually recycle images, sounds, and themes, and in some cases reintroduce story- telling strategies throughout my films. It’s as if they’re linked through their DNA.”

Berliner, who meticulously edits his films, says “I’m not editing so much as inventing my films as I work on them… I have faith in the very idea of process – that I might start somewhere, think I’m headed in a particular direction, make all sorts of wrong turns trying to get there, then realize I’ve been mistaken and begin to rethink and reorient where I’m going and how I might get there.”

Yet there’s a common thread that makes his work continually interesting. I’ve been a fan of Berliner for many years now so I was immediately excited when I heard that he recently released a new feature film through HBO. I got this one as a download through iTunes and as far as Berliner being Berliner, I was not disappointed.

FIRST COUSIN ONCE REMOVED (2013) is a harrowing and unflinchingly honest portrait of a poet and an intellectual slowly losing his memory to Alzheimer’s disease. With Berliner’s unmistakable touch, it’s also another meditation on identity, memory, and family.

FIRST COUSIN ONCE REMOVED (2013) is a harrowing and unflinchingly honest portrait of a poet and an intellectual slowly losing his memory to Alzheimer’s disease. With Berliner’s unmistakable touch, it’s also another meditation on identity, memory, and family.

The film presents poet Edwin Konig, front and centre, an elderly man who struggles with remembering but Berliner is always nearby with reminders and loud questions. Yet, it’s really through Berliner’s other voice – through his craft and art of montage – that we get a cumulative glimpse of the subject’s very soul. And it is on Berliner’s visceral fear that the audience hangs onto, however painful. We are scared along with him that we are seeing ourselves in the future: slowly losing one of the most exceptional brains of our time, a gleaming admirably complex and brilliant filing box of memory.

For a student of Berliner’s films, I watched FIRST COUSIN in awe of how much his previous films were, in ways, mere rehearsals for this one. I admire the fearless upcycling of his previous cinematic tricks. I was once again entertained by Berliner’s obsessive and meticulous ordering of visual sets: diary entries, photographs, same archival footage pop ups, same typewriter sounds, etc.

It was shot over a five year period but we are not given a chronological study of decline and loss. The film is organized in a kind of fractal way and he gives it to us all-at-once and no-holds-barred through editing, he carefully nests ideas of joy and wonder in complicated layers of personal pain.

In describing his creative process, he evokes the kind of openness and surrender required of the author for the material to organize itself.

“[In starting a project] I ask: what can I learn about myself from that kind of investigation… I decided to activate it; I decided to awaken it and contact all these people and not only see what kind of answers I might get from them but what kind of questions they would cause me to ask about myself… You throw the net into the water, you don’t know what it’s gonna bring back…”

His choice to use the words “activate” and “awaken” makes me think again of Story as living beings. Alan Berliner seems to have tapped into his own very particular way of self-expression through a comfort with uncertainty.

The process he describes with his work resonates with how I see my own. To binge-watch all of his movies together in one sitting is to easily see them like chapters in a long cinematic book that, as long as Berliner answers the call, will yet continue to be written.

Being the fanboy that I am, you can bet that I’ll be first in line for the next installment.